An atlas of work

The photographer was thought to be an acute but non‑interfering observer – a scribe, not a poet. But as people quickly discovered that nobody takes the same picture of the same thing, the supposition that cameras furnish an impersonal, objective image yielded to the fact that photographs are evidence not only of what’s there but of what an individual sees, not just a record but an evaluation of the world.

Susan Sontag, On Photography, 2004

This passage by Susan Sontag provides an effective introduction to the extraordinary documentary work that Alessandro Mallamaci has carried out on the heritage preserved in Calabria’s company museums. To fully grasp its value, one must consider the combination of two fundamental elements of the photographic act.

The first concerns the intention behind the photographer’s gesture and relates to his visual approach and to the extent to which it is capable of transforming and recontextualizing the object placed before the camera. In the images collected in this volume, objects drawn from a complex context such as the museum are elevated by the author’s gaze into icons of the entrepreneurial histories they embody.

The second element lies in the difference between human visual perception and the optical recording performed by the photographic device: photographs reveal details that escape the direct experience of a museum visit.

Making objects the protagonists of this narrative means recognizing them as primary elements of a new and necessary vocabulary through which to decode and reread the industrial and social history of a region where the culture of work and the specificity of its territories constitute a heritage to be preserved and enhanced. The result is a narrative capable of delving deeply into individual company histories while simultaneously outlining an unprecedented critical geography of Calabria.

Ten institutions are involved in the project: the “Giorgio Amarelli” Licorice Museum in Rossano Calabro (CS), guardian of the ancient history of licorice cultivation and processing by the Amarelli family; the Callipo Museum, dedicated to the historic canning company founded in the early twentieth century in Pizzo (VV); Gias Experience in Mongrassano (CS), an experiential museum narrating the story of the company that revolutionized the frozen food market; the Lanificio Leo Museum in Soveria Mannelli (CZ), where visitors encounter the full production cycle and retrace the history of one of Calabria’s oldest textile enterprises; Vi.te.s., the museum space of the Librandi winery in Rocca di Neto (KR), where new technologies applied to oenology coexist with ancient viticultural knowledge; Celestino, the Museum of Broom, Wool, and Silk “Eugenio Celestino” in the heart of Longobucco (CS), offering an immersive experience of the production cycles of these three natural fibers and the history of local manufacturing; the Bergamot Museum of Reggio Calabria, recounting centuries of labor and entrepreneurship linked to the cultivation and processing of bergamot; the Pane di Cuti Museum in Figline Vegliaturo (CS), where bread-making traditions are preserved and renewed; CARTA, the museum of the Rubettino publishing house in Soveria Mannelli (CZ), focusing on the relationship between tradition and new technologies; and finally, the Terme Caronte Museum (CZ), where the history of the enterprise and the Cataldi family intertwines with that of Italy itself.

Within the visitor itineraries designed by most of the museums involved, the narrative tends to emphasize—often through experiential approaches—the connection between roots, history, innovation, and the future.

In this volume, Mallamaci’s photography offers a different, almost contemplative experience. Viewers are invited to move through the pages and imagine what the images, though not explicitly depicting it, are able to evoke: a time distant from the present; a society and landscape in which these companies served as solid points of reference; hands and eyes working with rhythms and gestures we have now forgotten; voices and sounds once inhabiting workspaces.

Each image stimulates curiosity, generating a continuous oscillation between objects that feel familiar and others we wish to know more about—to understand their function or to guess their date. The history of companies intertwines with that of civilizations, technologies, and materials, as well as with graphic design and communication: raw materials, tools, machinery, packaging, signage, and documents follow one another without interruption.

Faced with a heterogeneity of subjects and spaces, Mallamaci adopts a set of coherent linguistic choices: generally neutral and material backgrounds, the use of natural light, and a preference for shallow depth of field. These choices restore to the photographed objects an autonomy often absorbed in museums by exhibition rhetoric and the distancing effects of display. Natural light enhances their sculptural value, while neutral backgrounds and limited depth of field invite concentration on form, matter, and sign. The photographer’s gaze skillfully guides that of the reader, encouraging them to listen to the images and to linger on what details can reveal. Material consistency, imperfections, scratches, cracks, signs of wear, and patinas thus become the space in which the very function of company museums is expressed: to preserve and protect the memory of the past while building a bridge to the present, where community identities are renewed within the continuity of territorial productive traditions.

In Mallamaci’s photography, and in this body of work, documentary rigor coexists with poetic rendering. What might appear to be a mere catalogue is instead a visual and cultural—indeed, emotional—atlas, in which each image constitutes a fragment of a broader discourse. In the reader’s hands, the volume functions almost like an “Aristotelian telescope,” where each object does not end in itself but becomes a catalyst for thought, evoking the world to which it belongs and questioning the future that will preserve it as a precious asset, a testimony to the history and evolution of technologies and production.

Chiara Ruberti

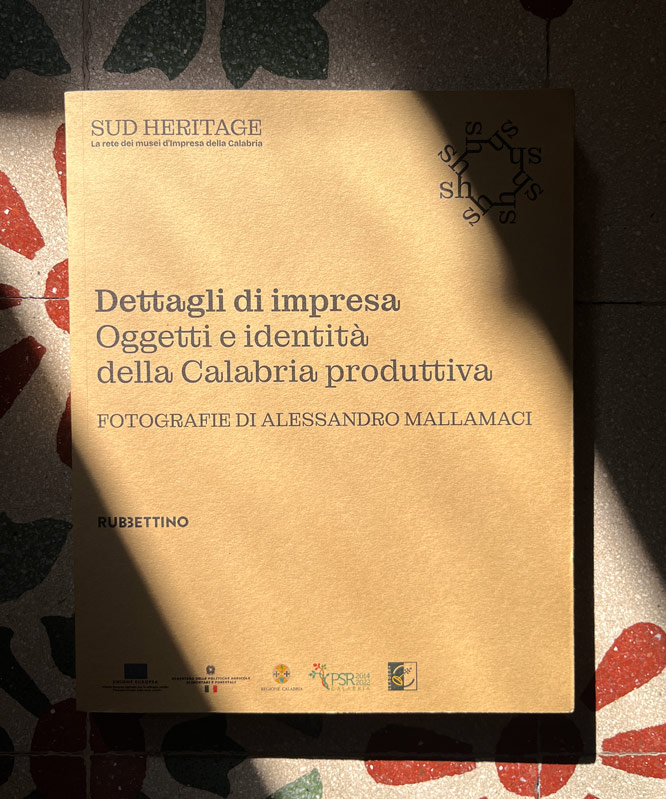

Dettagli di impresa, Oggetti e identità della Calabria produttiva, fotografie di Alessandro Mallamaci

ISBN 9788849887617